Syrian president Assad has set up an institute to revive interest in the language of Christ

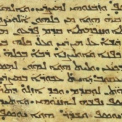

A stone ossuary bearing the inscription in the ancient Aramaic language ‘James, son of Joseph, brother of Jesus’ Photograph: Biblical Archaelogy Society/Corbis Sygma

Ilyana Barqil wears skinny jeans, boots and a fur-lined jacket, handy for keeping out the cold in the Qalamoun mountains north of Damascus. She likes TV quiz shows and American films and enjoys swimming. But this thoroughly modern Syrian teenager is also learning Aramaic, the language spoken by Jesus.

Ilyana, 15, is part of an extraordinary effort to preserve and revive the world’s oldest living tongue, still close to what it probably sounded like in Galilee, now in Israel, on the brink of the Christian era.

„In Nazareth when Jesus was born they spoke more or less the same language as we do in Maaloula today,” said teacher Imad Reihan, one of the pillars of this picturesque village’s Aramaic Language Academy, where Barqil is studying.

„Eli, Eli, lama sabachtani” („My God, my God, why hast thou forsaken me”) – Christ’s lament on the cross – was famously uttered in Aramaic.

Recognised by Unesco as a „definitely endangered” language, Aramaic is spoken by 7,000 people in Maaloula, dominated by Greek Catholics (Melikites) whose churches and rites long pre-date the arrival of Islam and Arabic. Western Neo-Aramaic, to use its proper linguistic title, is spoken by about 8,000 others in two nearby villages, one now wholly Muslim.

Aramaic’s long decline accelerated as the area opened up in the 1920s when the French colonial authorities built a road from Damascus to Aleppo. Television and the internet, and youngsters leaving to work, reduced the number of speakers.

Nowadays, many local men are away driving the huge refrigerated trucks that cross the desert to Saudi Arabia. Still, many old traces remain: in nearby Sidnaya, worshippers at the Church of Our Lady speak Arabic with a distinct Aramaic accent.

But things are definitely looking up. „When I was at school over 30 years ago, we were not allowed to speak Aramaic,” said Mukhail Bkheil, standing behind the counter in Abu George’s souvenir shop in Maaloula’s main square, where buses disgorge tourists visiting the beautiful Church of Mar Takla, an early Christian martyr, in a grotto on the steep cliffside. „Now, thanks to President Assad, we even have an institute teaching it.”

Bkheil’s party piece is reciting the Lord’s Prayer in Aramaic. But he chats freely to friends, underlining the fact that the language is alive and well, not just liturgical.

Saada Sarhan, the language academy administrator, learned Aramaic as a child and is teaching her own children, but often feels social pressure to speak Arabic when non-Aramaic speakers are present. „Otherwise it’s rude,” she says.

Improbably, Aramaic was given a boost by a Hollywood film, Mel Gibson’s controversial Passion of the Christ, released in 2004 before the academy was set up.

Founded by the University of Damascus with government help, its modern premises boast a bank of PCs, new textbooks, a teaching staff of six and 85 students at three different levels.

Elias Taja is another of them: this native Aramaic speaker and retired maths teacher wanted to learn how to write the language. „I talk to my wife and daughter Miladi only in Aramaic though my daughter does sometimes reply in Arabic,” he explained over cardamom-flavoured coffee and locally grown pears.

Miladi, 25, recently married a man from Sidnaya who does not speak Aramaic. Taja worries she will not manage to pass it on to her children – his grandchildren.

Syria being Syria, there are political sensitivities, not least because „Arabisation” was a key feature of government education policy after the Ba’ath party came to power in the 1960s.

„In Syria there are a lot of minority groups: Circassians, Armenians, Kurds and Assyrians, so it’s a big decision to allow the teaching of other languages in government schools,” said Reihan. „But the government is interested in promoting the Aramaic language because it goes back so deep into Syria’s history.”

Observers say the opening of the Aramaic academy showed a more relaxed and confident attitude by the regime. Scholar George Rizkallah dedicated his 2007 Aramaic textbook to the „great leader and patron of the sciences and education Dr Bashar al-Assad”. A large portrait of the president hangs in the principal’s office, as in all public buildings in Syria.

Considering the bitter enmity between Syria and Israel, which still occupies the Golan Heights, it is striking that Aramaic letters are so similar to the Hebrew used in rabbinic texts; one reason, perhaps, why the only Aramaic sign in Maaloula is on the academy. „Otherwise people might think some buildings were Israeli settlements,” joked one visitor from Damascus.

Linguistic experts say that Syria is doing well in fostering this part of its heritage. „Aramaic is actually pretty healthy in Maaloula,” said Professor Geoffrey Kahn, who teaches semitic philology at Cambridge University. „It’s the eastern Aramaic dialects in Turkey, Iraq and Iran that are really endangered.”

Reihan and colleagues were delighted recently when a Unesco team came to visit and hope for funds to allow them to collect vanishing words into proper dictionaries. The teaching, meanwhile, goes on.

Ilyana started classes last November. „My father speaks Aramaic but my mother doesn’t as she’s from Lebanon,” she said. „I speak OK already but I’m going to carry on as I want to become fluent. I don’t know too much about the Aramaic language but I do know that it’s ancient.”

Forrás: http://www.theguardian.com/world/2009/apr/14/aramaic-revival-syria

Ha tetszik írásunk, ajánlhatja másoknak is!

A túlélés útja ma magyarul gondolkodni...

Európa szívéből

Európa szívéből